Em 1990, Sanaz Zadegan nasceu em Portugal. Em 1950, a sua mãe nasceu no Irão. Em Setembro de 2022, Mahsa Amini, uma mulher de 22 anos, morreu em Teerão após ter sido detida pela polícia da moralidade. Hoje, dia 8 de março, partilhamos esta história contada por Sanaz Zadegan, para lembrar e homenagear Mahsa Amini, os protestantes no Irão, e a luta pela igualdade.

Author: rose

-

The Story of Noncia

Alfreda Noncia Markowska was a Roma woman that saved 50 people during World War II.

-

Ninguém Dorme na Rua

Nobody Sleeps on the Street

Seven people who are or have been in a situation of homelessness share their life stories, revealing the social issues that underlie this situation.

Documentary

Watch the full documentary via Zero em Comportamento

Podcast

-

Histórias da Nossa Terra

Four people from Brazil, Eritrea, Syria, and Colombia share stories, chosen and narrated by themselves

-

BABEL Magazine #2

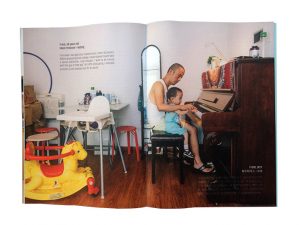

My Name is Jinxi

29°03’N × 120°13’E | interview by Maria AB

“My name is Jinxi. I am 30 years old and was born in Zhejiang Province.

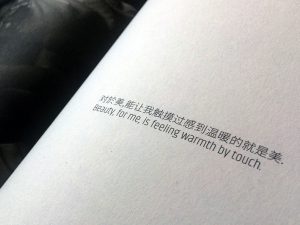

As a child I had very limited eyesight. I could not see clearly most of the time, but sometimes, if I looked closely, I could read words with large font in books and could write Chinese characters.

As I grew up, my vision continued to decrease, until all I could see was light and shadows.

Growing up, I played with other children, and received support from my teachers and other students.

However, I was not aware that I was different from other people. I did not know I had a disability. I did not even know what a disability was.

I did not understand that disability was an issue until after I completed my first master’s degree.

At the time, I was trying to find a job and submitted my CV to teach in a school.

I was called for an interview, but when the headmaster met me, he was noticeably surprised.

He asked me, “If a student is using a cellphone in class, would you be able to notice it?” I told him that if they use it without sound, I could hardly notice it. But I also told him that if I teach well and create attractive classes, then they would pay attention to the class and not play with their phones.

The headmaster did not agree with me; if a teacher cannot catch a student using a phone, then they cannot be a good teacher.

This was the first time I faced the barriers of disability.

I did not know what do, or how to respond. I was not aware of disability rights. I felt confused about other people with disabilities. How do they apply for jobs?

This was a very significant event in my life: I realized that people with disabilities come across many challenges in the society, and I felt motivated to know more about disability rights.

I still had not met anyone with disabilities, but I started researching about the disability community and disability rights.

I found some broadcast programs made by visually impaired people on the Internet, and magazines made by people with disabilities. But it wasn’t until I found the opportunity to do an internship with an organization that works with people with disabilities in Beijing, called One Plus One, that I got to know the real situation of the community. For the first time I worked and lived with people with disabilities, and understood the barriers and the challenges in society that affect this entire community. This has led me to devote my life to the protection of disability rights.

Nowadays I’m a lawyer and I advocate for equal rights for people with disabilities. I represent people at court, I provide legal counseling, and I do legal research on the enforcement of disability rights.

But advocacy is not just my job, it is my whole life.

I engage with people around me and I let them know more about my life. Many are curious about the way I live independently and want to support blind people but do not know how.

I show taxi drivers the screen reader in my phone that allows me to call and track an Uber. I explain to staff in hospitals, grocery stores, public transport services, and government offices what they all can do to support people with disabilities in their facilities.

I show people how to guide a visually impaired person: do not grab our arm, just let us hold your shoulder, and walk on.

Everyday I try to make people around me know more about disability, and I try to know more about places that provide equal opportunities to people with disabilities.”

“I dream and I fight for a future in which people with disabilities in China can live without barriers.”

…

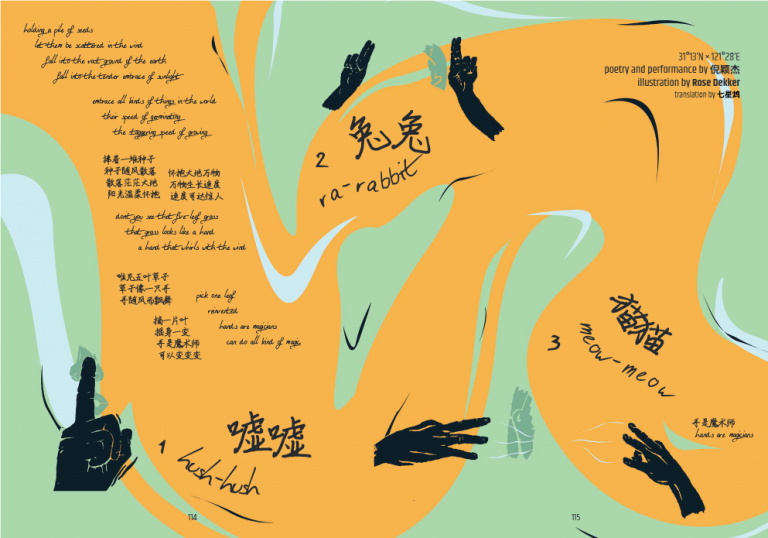

Sign Language Poetry

31°13’N × 121°28’E | written and performed by 倪颖杰 | illustrated by Rose Dekker

…

Contact us to order a copy of Babel magazine!

-

BABEL Magazine issue 1

BABEL Magazine issue #1

Jane’s Story

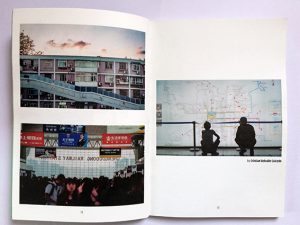

23°01’N × 113°44’E | by Rose Dekker

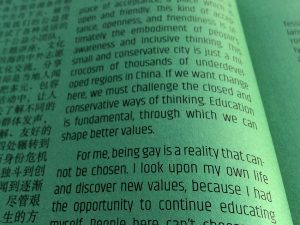

“I came out to my parents almost two years ago. We haven’t had a very good relationship since then. They think it’s against God’s will. I went home during the Mid-Autumn Festival, and we had a really big fight. My dad told me that if I am not going to change my lifestyle, then that’s the end. My mom shouted at me and said: ‘How can you face God?’”

Jane Hu grew up in Dongguan, Guangdong province, with her parents, her younger brother, and her sister. Born to two Catholic parents, religion has always been a big part of her life. “When I was in primary school, we went to church every Saturday and Sunday, but other kids in my class didn’t. I didn’t want them to know about it, because I was afraid they would ask me questions and think I’m different. But when I was a teenager, my thoughts started to change. You think you’re different and you’re more special.”

Jane didn’t talk about her religion with anyone in high school until she saw one of her best friends wearing a crucifix necklace. She asked her about it, and it turned out the girl was also Christian. From then on, they often went to church together.

When Jane was fifteen, she decided she wanted to be more independent. Her mother rented a room for her in the same city. “When you’re fifteen, it’s an amazing time to live alone. You have your own place without your parents, you can sleep whenever you want to sleep. You can go out. You can decide not to come home. During that time, I went out a lot. I had a very nice time. The best time of my life, I guess.”

Despite not living with her parents, Jane still went to church.

“My mom is very religious. When something happened, she would say, ‘Jesus arranged this.’ This is very weird for me to hear. I could take it if you would say it’s destiny, but when you say somebody, or some god, arranged this thing for you, it sounds very limiting. In university, I started to have my own thoughts about what religion is. I remember I had a big fight with my mom about whether Jesus really existed or not. By that time, I did have religious beliefs inside of me, but I didn’t think about whether it was this god or another god. But I did believe there is something out there.”

As part of university, Jane studied abroad in Indonesia, where she went to church more frequently. “I think it was because I was alone and in a different country. Whenever I enter a church, it gives me a sudden kind of peace. I can just sit and think about things very peacefully. It’s a safe place for me to go.”Jane met her girlfriend, Ana, in Indonesia. They decided to move to China together. “The first thing I did when we went to China together was to bring her to my hometown. My parents do not speak English, so I was basically translating everything. It was very awkward. My mom asked me, ‘Who is she?’ I told her, ‘She’s my friend’. By that time, my sister already knew that Ana was my girlfriend, but nobody told my parents. We decided not to, because we were having a hard time at the time, and we felt like it was not a good idea.”

Jane did not tell her parents about her relationship with Ana for two years. “People kept introducing me to boys and boys and boys. I told them that I didn’t want a relationship, that I wanted to focus on my career. I thought of millions of reasons to make them stop bothering me.”

Even though she hadn’t told her mom, Jane suspected her mom already knew about her girlfriend. “Sometimes when my mom saw the news, she would tell me, ‘You know, there are gay people — actually quite many in Shenzhen.’ And I would think, “Why would she tell me this? Maybe she knows already?” It was very weird, but I was very happy, because I thought maybe she was OK with it, maybe she wanted me to tell her.”Jane tried to come out to her mom twice. “I said, ‘Can I ask you something? What if, just what if, I’m a lesbian?’ My mom replied, ‘Come on! Are you kidding?’ Then we started talking about something else. That was the first time. I was so scared to tell her, but she didn’t take it very seriously, because I was young. The second time was the time she told me about the news. Then I asked her, ‘What if one of your daughters is gay?’ She said, ‘I would kill any one of you if you were gay.’ She was laughing when she was saying this.”

After being in a relationship with Ana for two years, Jane’s mom started calling. “‘Why don’t you want to have a relationship? How come you don’t have a boyfriend? Why, tell me why?’ She was pushing me and pushing me. I was so tired of making up excuses. So I told her, ‘I have a girlfriend.’ And she said, ‘What? A girlfriend?’ And I said, ‘Yes, a girlfriend. Ana is my girlfriend.’ She couldn’t understand what I was saying: ‘What are you talking about?’ She was processing it, and I said, ‘Yes, mom, a girlfriend. I’m a lesbian.’”

“I didn’t talk to her for a month, maybe two. When she called me, I didn’t answer, because I didn’t want to see her face, and I didn’t want to talk about it. Actually, I regretted telling her under these circumstances. I had planned it so well: I wanted to educate my mom step by step, so she could be more open-minded about it. I was going to give her books and videos and everything. But then I just couldn’t take it anymore, and told her.”

“My dad started to text me. He wanted to know about my life. My mom didn’t tell him what I had told her.

Jane did not have a close relationship with her father, so she was very surprised with his sudden interest in her. “And then once, he yelled at me: ‘I just want to know your life! I just want to get to know you! I know we don’t have a very good relationship!’ He said this in a very harsh way. We are very similar in our temper, our character, so I answered him, ‘Oh, you really want to know my life? Then I have something to tell you.’ And then I told him that I had a girlfriend.

“He deleted me. He didn’t reply anymore. When I texted him, ‘How are you?’, I couldn’t send the message.“Then, one early morning at 4am, he sent me voice messages, maybe five, of 60 seconds each. He told me that it is wrong, and that if I cherish our relationship, I shouldn’t do this. That I should break up with my girlfriend, go home, and that he would pretend nothing had happened. I couldn’t answer. I couldn’t say anything. I knew at that time that nothing I said could change what he thought. Even now, whenever I see him face to face, he tells me exactly the same thing.”

“My brother and sister are fine. We have a good relationship. They knew that I was in a relationship with Ana before my parents knew. They were very supportive. They told me, ‘It’s your life, it’s fine. You should grab your chances, and if this is you and this is how you want to live, that’s it. No one should tell you how to live.’

“Nobody else knows in my family. Every time, when people ask how old I am – I’m 26 – they think ‘Oh my God, so old, and she doesn’t even have a boyfriend!’ It’s not their business, but they care a lot.”Jane’s parents’ disapproval goes beyond religious reasons. Where she comes from, people care a lot about “face” and reputation. “In the beginning of this fight, I said very straightforwardly to my parents, ‘I know, you just care about face, so you don’t have to tell anybody. It’s my life, not yours. If anybody asks me, I will not tell them if you don’t want me to.”

But there were other concerns.

“Both my mom and dad thought that in this kind of relationship I cannot have a baby. It’s very important for them to have a child who can take care of them in the future. They also said I cannot get married in China. Those were the two main reasons they were telling me, so I told them I can get married somewhere else, and I can have babies. They have different views. They are from a different generation. They think that this kind of lifestyle does not guarantee your future. But even in an “ordinary” relationship, you could get divorced.“They think I will not be happy, that people around me will judge me because of this. They don’t want me to live a miserable life. I told them that the people around me are fine, that the times are changing and people can accept this.

“I always told my parents they can take as much time as they want. I told them I don’t want them to understand my lifestyle; I just want them to accept who I am, and the way that I want to spend the rest of my life. They just couldn’t take it.“My mom is getting a little bit better. Sometimes, she asks about Ana. It’s very interesting, she can be yelling at me about that topic and then the next thing she asks is, ‘How is she?’

“Before I went home for the Mid-Autumn Festival, I thought that things would go better. But then we had this big fight. My mom was crying and throwing things on the floor. She was saying, ‘You don’t deserve to be judged by these people.’ I was crying when she said this.”

“I do pray before I sleep, every night. I pray when I have bad things happening in my life. I do seek help from Jesus. I do talk to Jesus and think he’s listening. And when I travel, I do the same thing my mom did when we were younger — I pray. It’s a quite complicated situation, I think. I cannot say I completely dedicate myself to religion, but I also cannot say I don’t believe.

“Sometimes, when my mom can’t fight me, she brings up things form the Bible. ‘God doesn’t accept gay people; gay people are sinners.’ She would take out the Bible, and read the verses to me. She told me that God would not accept this, and it is against God’s will.

“Once I talked about my sexuality during confession in church. I told the father that I’m a girl (in case he couldn’t hear it) and that I have a girlfriend. He asked me, ‘Why did you decide to tell me now?’ The next question was, ‘Do you think God would approve your lifestyle?’ He asked me several more questions, but he didn’t tell me what he thought about it, or what I should do. He said he didn’t need my answers, because he wanted me to answer them for myself. Then he said that God loves who we are. So for Him, it’s not a big deal, which is something I also believe in. And I want to live my life this way. There’s nothing wrong about that, and I don’t need to change it.”

…

Previous

NextContact us to order a copy of Babel magazine!

-

Human Stories

Karim’s Story

Stories of people that are not often heard, in English.

Listen here

My name is Karim. A lot of people don’t know my country, it’s a very small country in East Africa. I’m in Portugal since maybe one year, like since last June.

And yeah, so I’m an asylum seeker in Portugal and I’m a homosexual from the LGBTQ community. And now I’m living in Lisbon, and there I’m working.

The home that I grew up in, for me it was some kind of sadness. I can say that. Like a little bit of… not really a jail, but a mindset, something like that, something against everything that I was thinking. And the childhood that I lived there, it wasn’t… it wasn’t the best.

So I was born in not a big family and not small, with like two sisters, one brother, me and my parents. My parents, like my family, they’re very traditional, very religious. So I grew up in this kind of atmosphere, and always for me, since my childhood, it wasn’t easy, because I had some manners like that… Like the way that I was talking, when I was a child, and they were always here to educate, how should I talk, what should I say – don’t talk like this, like that; stay with my uncles, because that part is for men, not for women.

So I remember until today I had these trousers, very beautiful, with flowers and everything, that I bought with my own money. And my mother took scissors and cut it, because like, no, it’s for girls, how will you wear this?

And home for me wasn’t a normal thing, the mother, the father… they were always with my big brother, because in my tradition, in my family, always men are more important than women, so this is why my big brother was the little love of my parents, and I was the one that… no.

The only one that I was very close in my family was my sister, she was like the psychologist since always. Every time I was sharing with her, so she was here to motivate me.

When I grew up in this family, I’m always someone who asked a lot of question. I’m Arabic, and I can understand the exact meaning of the Quran. So when I understand the meaning of the Quran, I started asking questions. This is when the trouble starts. I was like a child, 10 years old, 11, so for example, when you pray, like a Muslim, it’s always one sentence, “the people who will go to hell,” something like that, and I say like it’s not logic, and the answer was, “you’re denying what god is saying, you’re against god,” and I remember that in that day my mother slapped me, to educate me.

What happened at home wasn’t exactly like in school. Because when I was at school, when I was a child, I had the best marks, and I was the first one in class, so it was a little bit two worlds in my life.

So it was the home and the school.

Till now I can say the only thing that helped me, really helped me, were the comments I was having from my teachers. Like, “you always have a new idea,” always a good comment, it wasn’t like my family.

Since my childhood I understood I’m not like this kind of men, who will say, “ah this girl is beautiful.” I remember my big brother had a best friend, and he was handsome, and I loved to play with him when I was a child and in middle school, and it wasn’t like a normal friendship for me, maybe he was my first love.

The feeling that I’d always had when I’d see boys it was a bit strange, it wasn’t a normal feeling, it wasn’t like a friendship, so of course I was always asking myself, ‘what is this feeling?’, so I started to search. I saw that there’s people like me existing in this world. I discovered that there is gays, something called gays.

This is when I realized that there is homosexuality and after that I realized that it’s not a crime. They always say that homosexuals are [people of Lut], and that god will kill them, because they commit a very big crime. I don’t believe in that.

In my country, being homosexual, you cannot even say it, you cannot pronounce this word. It’s a little bit like forbidden to be homosexual. The word homosexual doesn’t exist in their mouths, it’s always, like, how can I say in English, like faggot, very homophobic words, and even if you talk like girls, when someone insults you, hurts you, slaps you, does something against you, you cannot go to tell, for example, “he’s homophobic, he did something like that”, it’s the person, it’s the homosexual, he himself who will go to jail. Because he should be a man, and not telling this. Maybe the police himself will be against him and slap him in the office, in the police.

When I met one guy I was in high school and we were friends, we became friends. At that time I had to adopt a certain way to talk. Because when you become very tired of “don’t talk like that”, you have to adopt this, to live in the society.

But Hasan, his name was Hasan, he couldn’t do it because it’s his character, it’s his manner to talk. I remember in high school they were calling him Hasna, the feminine name of Hasan, just to insult him. And when we became friends, I went to talk to him, and he was a little bit… it was strange that I was respecting him, like “why are you talking with me?”, not like the others.

So when I met him, I understood, and of course he understood too.

I remember he came one day to my home, like normal friend, and I remember my mother and everyone said, how do you have a friend like this? Yeah it was bad and after that he had a big trouble. And he was originally from a very, very small town, and they took him there, maybe they wanted to change him. So after that we didn’t meet again.

I was just trying to find a way to go and not to come back, and not to live in this kind of situation, because you can breath, but you cannot feel the oxygen. When I was there, for me it was like that.

I went to Turkey to study, it was the best day of my life.

When I moved I started a little bit to live my sexuality. The first thing I searched on Google when I went to Turkey was to dating guys. And the good thing, I can say it’s a very good thing, is that I wasn’t that religious, like my family. I met in my life Muslims homosexuals and they can absolutely not accept themselves. Always praying, I met a lot of this kind of guys in Turkey, for example, when we do, let’s say, sex, and after that, “why did I do this”.

And I wasn’t like that because every year that I grew up, and understand better the religion, it’s not a sin or wrong, or something that I’ll go to hell, because I’m from [people of Lut]. After this I realized that they’re wrong, not me. And I was explaining all this to the gay Muslims that I met, some of them felt a lot of comfort and saw that what I was speaking of was logic.

This best friend that I met, in Turkey, we were in the same university, and after two years of friendship she was always asking me, we are not in our country, why don’t you have a girlfriend, be free, so I was looking at her, should I say, no should I say, no, but one day I say.

She was very like “wow” at first, and she asked me a lot of questions, like what do you feel when you see a girl, what do you feel nanana, that kind of questions, because for her it was a new thing to meet one guy, because we were speaking exactly the same dialect, and she was a bit, ‘one who is speaking like me, from the same traditions like me, who’s like this, it really exists?’

So I met a guy when I was in university and I was in a relationship with that guy. Until that day my family did not directly know that I am homosexual. When things went wrong, went bad, with my ex-boyfriend, and he was an Arabic guy too, and he knew exactly the tradition with the Arabic families, how the situation is, and a little bit to hurt me, it’s not me who made the coming out to my family, it’s my ex.

And since that day, maybe 2 years ago, that I don’t talk with them until today, with my family. The last sentence that I can remember from my mother – I was talking with my mother, not my father that day – like, “I wish that you were not born. I wish to see you dead.” It was something like that, so I switched off my phone and continued my life.

Of course at that time I wasn’t very strong psychologically, but it was like a box ring, you know, when you take the shoot from the person in front of you and you still resist, psychologically, I was like that. I had always the motivation that everything will be fine, everything will be better, like when I had my sister with me, she was telling me that one day it will be okay, don’t bother yourself.

When I was at that time, like 18 years old, I lost her, my sister, because of the traditions of the family… She got married, but it wasn’t her choice, it was the family who choose.

So when I moved after Turkey, I came to Portugal, and I spent some months in Luxembourg. It’s there where I met the wrong psychologist, it was an old man, I will never forget him, he said to me, “is it in your country like in Iran for example, there’s a death penalty for homosexuals?”, I said, “no, it’s a crime, you can go to jail”, and he said to me, “maybe the jail is good for you”.

So I just looked at him like that and I just went from that psychologist, and when I couldn’t resist to that, everything in my life… I started to think about suicide. I never think about it, like seriously, I was thinking about it in high school, sometimes I had that idea, but it wasn’t that serious. I remember that in that day it was really serious. And I spent around one month and one week in the psychiatric department for my depression.

It was one of the good moments in life, it was that month, because I met a lot of people, and a lot of very good nurses, that can understand you, that can be next to you. I was discovering people who are good. And like, you’re not something wrong for them.

That feeling when you feel, when you explain something, and you have the feeling you’re not the wrong person in the world, it’s the best feeling that a human being can have.

After that psychiatric department, I met one psychologist, and she was an old woman, sometimes I talk to her, till now, she was very kind, and she helped me a lot.

And in June last year, when I came to Portugal, I started to have that kind of people too, for example in CPR [Portuguese Refugee Council]. Like the psychologist, she wasn’t like a psychologist, she was my friend.

The thing that was new, all people, all gays that I met, Portuguese, they’re like “so yeah I had a ex-boyfriend that was coming to my home, blablabla, and my mother knew”, for me it was strange. Like, it was what? Your family knows that you’re gay? It was new. But at the same time good and calm. Because I didn’t until today, when I say I’m an asylum seeker, or I am a homosexual, and I say that openly, I didn’t have a really bad reaction.

When you live with people that are not toxic, that have a little bit the same mindset, it’s the meaning of living peacefully.

Today I’m 24. I have talents that I discovered in myself after this whole situations, for example, I can easily understand people, help people who have problems.

And today also, not before, when someone is telling me, that doesn’t know me, that this girl is beautiful, I can say easily, “I don’t like girls.” And before I didn’t imagine one day that I will say this sentence easily. To be openly a homosexual.

In this journey of my life, when I saw a guy that comes from the middle east, that I met in applications, in gay apps, and when we talk, I saw and I understood that I wasn’t the only one who really lived in this trouble, with this community and family. What I want to do really one day is to do something for homosexuals in all these countries. Because homosexuals from an open country, like Portugal for example, Europe, the west countries, it’s not really the same thing, it’s not the same struggle as in orient. And I wish one day to help these LGBT people, and I hope that they will not lose hope.

It should not be one homosexual in this earth who should be sad. All homosexuals should be happy. All the LGBTQ+ community. Just that.

Eu chamo-me Karim, há muita gente que não conhece o meu país, é um país pequeno, no este de África. Estou em Portugal desde há cerca de um ano, acho que desde junho.

E ya, sou um requerente de asilo em Portugal, e sou homossexual, parte da comunidade LGBTQ. E agora vivo em Lisboa, e trabalho aqui.

Na família onde cresci… para mim era assim uma espécie de tristeza. Posso dizer isso. Assim um bocado… não exatamente uma prisão, mas uma mentalidade, contra tudo o que eu estava a pensar. A infância que eu vivi lá não foi… não foi a melhor.

Não nasci numa família grande, duas irmãs, um irmão, eu e os meus pais. Os meus pais, como o resto da família, eram muito presos às tradições, muito religiosos, e eu cresci nesse tipo de ambiente. E na minha infância, não era fácil, porque eu tinha umas maneiras, tipo a maneira como falava, quando era criança, e eles estavam sempre lá para me educar, como devia falar, o que devia dizer… tinha de ficar junto dos meus tios, tinha de ficar com os homens, não com as mulheres.

Lembro-me ainda hoje destas calças que eu tinha, mesmo lindas, com flores e tudo, que tinha comprado com o meu dinheiro, e a minha mãe pegou nas calças e cortou-as com umas tesouras, porque, “não, é para raparigas, como é que podes usar uma coisa destas?”

E a casa não era bem a coisa normal, a mãe, o pai… eles estavam sempre de volta do meu irmão mais velho, porque na nossa tradição, na minha família, os homens valem mais do que as mulheres, e por essa razão, o meu irmão mais velho era o menino dos olhos dos meus pais, e eu era aquele que… não.

A única pessoa de quem era próximo na minha família era a minha irmã, ela era como uma psicóloga, estava sempre a partilhar coisas com ela, e ela estava lá para me motivar.

Quando estava a crescer, naquela família, eu era sempre aquele que fazia imensas perguntas. Eu sou Árabe, consigo entender o sentido das palavras no Corão. E quando comecei a entender o significado do Corão, comecei a fazer perguntas. Foi aqui que começaram os problemas. Eu era uma criança, 10, 11 anos, e tenho este exemplo, quando rezas, como muçulmano, há uma parte em que se fala das pessoas que vão para o inferno, e eu dizia que isso não tinha lógica, e a resposta deles era, “estás a rejeitar as palavras de deus, estás contra deus”, e nesse dia a minha mãe deu-me uma bofetada, para me educar.

O que eu vivia em casa era diferente da minha vida na escola, porque quando andava na escola, quando era criança, eu tinha as melhores notas, era o melhor aluno da turma, e assim tinha quase dois mundos na minha vida.

A casa e a escola.

Agora posso dizer que a única coisa que me ajudou, que realmente me ajudou, foram os comentários dos professores, do estilo, “tens sempre ideias”, faziam sempre comentários positivos, não eram como a minha família.

Desde a infância que sei que não sou como os outros homens, que dizem, “ah aquela rapariga, que bonita”. Lembro-me que o meu irmão mais velho tinha um melhor amigo, e ele era atraente, e eu adorava brincar com ele quando era pequeno, e não era bem uma amizade como as outras para mim. Talvez ele tenha sido o meu primeiro amor.

O sentimento que eu tinha quando via rapazes era um bocado estranho, não era um sentimento normal, não era como na amizade, e então é claro que me questionava, o que é este sentimento, e comecei à procura. Descobri que há outras pessoas como eu no mundo. Descobri que há gays, uma coisa que se chama gays.

Foi assim que fiquei a saber que a homossexualidade existe e percebi que a homossexualidade não é um crime. Sempre me disseram que os homossexuais são “Gente de Lut”, que vão ser mortos por deus, que cometem um crime grave. Não acredito nisso.

No meu país, ser homossexual, tu nem sequer podes dizê-lo, não podes pronunciar essa palavra. É mais ou menos proibido ser homosexual, e a palavra homosexual não existe nas bocas deles, é sempre, como é que posso dizer, tipo paneleiro, palavras muito homofóbicas. E se tu falares como as raparigas falam, e alguém te insultar, te magoar, te bater, te fizer mal, tu não podes ir fazer queixa e dizer, por exemplo, “ele é homofóbico, ele fez-me isso”, vai ser a pessoa, vai ser o homossexual que vai acabar preso. Porque deves ser um homem, e não deves dizer estas coisas. Talvez a própria polícia te bata na esquadra.

Eu conheci um rapaz quando andava na escola e éramos amigos, tornámo-nos amigos. Por essa altura, eu tive de adotar uma maneira diferente de falar. Torna-se cansativo estar sempre a ouvir, “não fales dessa maneira”, então tens de te conformar, para viveres em sociedade.

Mas o Hasan, o nome dele era Hasan, ele não conseguia fazer isso, era a sua maneira de ser, a sua maneira de falar. Eu lembro-me que na escola estavam sempre a chamar-lhe “Hasna”, a versão feminina de Hasan, só para o insultar. E quando nos tornámos amigos, foi quando fui falar com ele, e ele ficou uma bocado… foi estranho, eu respeitei-o, do tipo, “porque é que estás a falar comigo?”, ao contrário dos outros.

Quando o conheci, eu entendi, e é claro que ele também entendeu.

Lembro-me de uma vez em que ele foi à minha casa, como um amigo normal, e lembro-me de a minha mãe e toda a gente dizerem, “como é que tens um amigo destes?”, ya, foi mau.

Depois disso ele teve grandes problemas. A família dele vinha de uma vila muito, muito pequena, e levaram-no para lá, se calhar para mudá-lo. Depois disso, nunca mais o vi.

Eu estava só a tentar encontrar uma maneira de ir embora e não voltar, não viver mais aquela situação. Porque podes respirar, mas não há oxigénio. Quando eu vivia lá, para mim era assim.

Fui estudar para a Turquia. Foi o melhor dia da minha vida.

Quando me mudei para a Turquia, comecei a viver um bocado a minha sexualidade. A primeira coisa que procurei no google foi encontros com rapazes. E a coisa boa, posso dizer que é mesmo uma coisa boa, é que eu não era muito religioso, não como a minha família. Na minha vida, conheci muçulmanos homossexuais que não se aceitam completamente a si próprios. Estavam sempre a rezar, conheci muitos rapazes assim na Turquia, por exemplo, quando fazíamos sexo, depois perguntavam-se, “mas por que é que fiz isto”.

E eu não era assim porque a cada ano que passava, eu percebia melhor a religião, e que não é um pecado ou errado, ou alguma coisa que me vai levar para o inferno, por ser “de Lut”. Percebi que eles é que estão errados, eu não. E expliquei isto a todos os gays muçulmanos que conheci, e alguns deles sentiram algum conforto e viram que aquilo que eu dizia tinha alguma lógica.

A minha melhor amiga, na Turquia, andava comigo na universidade, e depois de dois anos de amizade ela continuava a perguntar-me, “não estamos nos nossos países, porque é que não tens uma namorada, sê livre”, e eu olhava para ela, digo, não digo, digo, não digo, e um dia disse-lhe.

Ela ficou muito tipo “wow”, e fez-me imensas perguntas, do estilo, o que é que sentes quando vês uma rapariga, o que é que sentes nanana, esse tipo de perguntas, porque para ela era uma coisa nova, porque falávamos o mesmo dialeto. Ela estava assim, “um que fala como eu, com as mesmas tradições que eu, e é assim, existe mesmo?”

Conheci um rapaz quando estava na universidade e comecei uma relação com esse rapaz. Nessa altura, a minha família não sabia com clareza que eu era homossexual. Quando as coisas não deram certo com o meu ex-namorado, e ele também era um rapaz Árabe, e conhecia bem as tradições de famílias Árabes, como a situação é… e para me magoar… não fui eu que fiz o meu “coming out” à minha família, foi ele.

E desde esse dia, há talvez 2 anos, que não falo com nenhum deles, com a minha família. A última frase que me lembro de ouvir a minha mãe dizer – nesse dia, eu falei com a minha mãe, não falei com o meu pai, foi algo assim, “preferia que não tivesses nascido”, “preferia ver-te morto”. Foi uma coisa assim. Desliguei o telefone e continuei com a minha vida.

É claro que nessa altura eu não era muito forte psicologicamente, mas era como estar num ringue de box, e levas um murro da pessoa à tua frente, e aguentas, mentalmente. Eu era assim.

Sempre tive a motivação de que tudo vai correr bem, de que tudo vai correr melhor, como quando tinha a minha irmã, e ela dizia-me que um dia tudo ia ficar bem, para não me preocupar.

Quando tinha uns 18 anos, perdi a minha irmã para as tradições da família, ela foi casada, sem escolha, foi a minha família que escolheu.

Depois da Turquia, vim para Portugal, mas passei uns meses no Luxemburgo. Foi lá que conheci o psicólogo errado, era um homem mais velho, nunca me vou esquecer dele. Ele disse-me, “o teu país é como o Irão, há pena de morte para homossexuais?”, e eu disse, “não, é um crime, mas podes ir para a prisão”, e ele disse-me, “talvez a prisão seja um bom lugar para ti”.

Eu olhei para ele e fui-me embora daquele psicólogo, e quando não consegui resistir a esta situação, tudo na minha vida… Comecei a pensar em suicídio. Nunca penso nisso a sério, às vezes na escola secundária pensava nisso, mas não era a sério. Lembro-me que naquele dia foi a sério. E passei um mês e uma semana no departamento de psiquiatria para tratar da minha depressão.

Esse mês foi um dos bons momentos da minha vida, conheci muitas pessoas, e muitos bons enfermeiros, que me entendiam, que estavam do meu lado. Estava a descobrir pessoas que eram boas. Não viam nada de errado em mim.

Esse sentimento, quando explicas uma coisa, e tens a sensação de que não és uma pessoa errada no mundo, é a melhor sensação que um ser humano pode ter.

Depois do departamento psiquiátrico, conheci uma psicóloga, uma mulher mais velha, às vezes ainda falo com ela, ela foi boa para mim, e ajudou-me muito.

E em junho do ano passado, quando vim para Portugal, também comecei a conhecer esse tipo de pessoas, por exemplo no CPR [Conselho Português para os Refugiados]. A psicóloga não era como uma psicóloga, era como uma amiga.

A coisa nova é, todas as pessoas, todos os gays que conheci, portugueses, eles dizem, “tinha um ex-namorado que ia lá casa, blablabla, e a minha mãe sabia”, para mim isto foi estranho. Tipo, como assim? A tua família sabe que és gay? Foi uma coisa nova. Mas ao mesmo tempo boa e tranquila. Porque até hoje, quando digo que sou requerente de asilo, ou que sou homossexual, e eu digo isso abertamente, nunca tive uma reação mesmo má.

Quando vives com pessoas que não são tóxicas, que têm mais ou menos a mesma mentalidade, isso é o que significa viver tranquilamente.

Hoje tenho 24 anos. Descobri alguns talentos ao longo disto tudo, por exemplo, consigo entender os outros, ajudar pessoas que têm problemas.

E hoje, ao contrário de antigamente, quando alguém que não me conhece diz, “aquela rapariga é bonita”, eu consigo dizer facilmente, “não gosto de raparigas”. Antigamente eu não imaginava que um dia viria a dizer esta frase facilmente, ser abertamente homossexual.

Ao longo da minha vida, quando saía com rapazes do médio oriente, que conhecia nas aplicações, nas gay apps, e quando falávamos, eu via e sentia que não era o único a viver esta luta, com a nossa comunidade e família. O que eu quero fazer um dia, é fazer alguma coisa pelos homossexuais destes países. Porque os homossexuais de países abertos, Portugal, a Europa, não é bem a mesma coisa, não é a mesma luta que é a oriente. E eu desejo vir a ajudar todas estas pessoas LGBT um dia, e desejo que elas não percam a esperança.

Não devia haver um único homossexual na Terra a sentir-se triste. Todos os homossexuais deviam ser felizes. Toda a comunidade LGBTQ+. É tudo.

-

Travessia

Six refugee women in Portugal take us along the paths they have travelled and across the borders they have crossed.

“I decided to protect my children

I decided to leave without anyone’s help

I decided to survive”

– Ajor, South Sudan

-

Why we use storytelling

Why we use storytelling

Humans are born storytellers. Humans have told stories for thousands of years – the art of storytelling likely started with the development of languages.

It is easier to remember something when told in story form and stories allow us to communicate through distance and time. Societies are created around stories.

Storytelling is thus an incredibly powerful tool that shapes the world we live in.

Stories & Science

When we listen to (or read) a personal story, our brain reacts differently than when we listen to facts. When we perceive a personal story, we are more engaged, intellectually and emotionally. This leads us to perspective-taking: we place ourselves in the shoes of the storyteller, guess their motivations, and try to predict what happens next.

The effect of this is that we empathize with the storyteller; we take on their perspective. This may help us understand a situation, or see the topic in a different light.

Besides, stories are more memorable and make us understand information better.

Stories as a tool to fight prejudice

Because stories help us see things from the storyteller’s perspective, it promotes understanding. The direct relationship between storytelling and reducing prejudice towards specific groups has been researched in several studies.

For example, a 2014 research by Hawke et al. found a reduction in stigma against people with bipolar disorder, and less desire for social distancing, after the participants watched a movie about people with bipolar disorder. In some cases, this effect was still in place a month after watching the movie.

Other research by Catalani et al. in 2013 in India shows that both a short, illustrated video and a feature-length film resulted in less stigma towards people with HIV/AIDS.

Chin, Rudelius-Palmer (2010) studied the effect of personal narrative on race and ethnicity, and came to the following conclusion:

“The basic power of stories lies in their potential to connect people to one another in fundamental ways that transcend issues of race and ethnicity through uncovering basic themes that strengthen the common bonds of humanity, as well as changing prevalent systems of oppression that perpetuate racial injustice.”

The studies all lead to a similar conclusion: personal narratives in various formats can combat prejudice around stigmatized communities.

Benefits for the storyteller

Storytelling is not only relevant for the person who listens or watches; it also benefits the person telling the story.

The cathartic and therapeutic effects of telling stories are well known. Telling stories helps us reflect and give meaning to our experiences. Because of this, it aids in personal development (Drumm 2013) and promotes resilience (East et al. 2010).

Not convinced yet? Take a look at our latest stories, and experience it for yourself!

Sources

- Austin, J., & Connell, E. (2019). Evaluating Personal Narrative Storytelling for Advocacy.Wilder Research.

- Catalani, C., Castaneda, D., & Spielberg, F. (2013). Development and assessment of traditional and innovative media to reduce individual HIV/AIDS-related stigma attitudes and beliefs in India. Frontiers in public health, 1, 21.

- Chin, K., & Rudelius-Palmer, K. (2010). Storytelling as a relational and instrumental tool for addressing racial justice. Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts, 3(2), 265-281.

- Drumm, M. (2013). The role of personal storytelling in practice. Institute for Research and Innovation in Social Services.Published on https://www.iriss.org.uk/resources/insights/role-personal-storytelling-practice retrieved on 17-11-2021

- East, L., Jackson, D., O’Brien, L., & Peters, K. (2010). Storytelling: an approach that can help to develop resilience. Nurse researcher, 17(3).

- Hawke, L. D., Michalak, E. E., Maxwell, V., & Parikh, S. V. (2014). Reducing stigma toward people with bipolar disorder: impact of a filmed theatrical intervention based on a personal narrative. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(8), 741-750.

-

Benefits of diversity & inclusion for companies

Benefits of diversity & inclusion for companies

Our societies are diverse.

Unfortunately, not all workplaces reflect this diversity, and even fewer manage to create a truly inclusive environment for the employees.

Diversity in companies is an easily measured fact: how diverse are employees in terms of gender, background, education, age, ability, sexual orientation, culture, and religion? If you want to increase diversity in a company – and as this article will argue, there are many reasons to do so – all you have to do is hire.

Inclusion is less obvious and requires more active participation of companies. If you want to learn more about how to become more inclusive, find out about our story-based inclusion program here.

There are many benefits to having diverse and inclusive companies. It is not only the right thing to do, but also benefits business in a multitude of ways.

A study by Deloitte (2013) shows that companies that have a diversity policy and in which employees feel included, perform better than other companies:

- They are more innovative

- Employees are more engaged

- Diverse teams collaborate better

- Employees that feel included have lower rates of absenteeism

These findings are backed by other studies.

A research by Boston Consulting Group (2017) studied which diversity drives innovation. In their study, they show that teams that have more diversity in terms of country of origin, industry background, gender, and career path, are more innovative. The same study shows that diversity in academic background does not result in more innovation, and a diversity in age actually has a negative effect on innovation in a company.

Another study by Forbes (2017) indicates that diverse teams make better, faster, and more successful decisions. In this study, it shows that teams that are diverse in terms of age, gender, and geographic background, make better decisions 87% of the time, they make decisions twice as fast, with half the meetings. When a decision is made and executed by a diverse team, it delivers 60% better results. A key finding shows that decision making improves, when diversity increases.

A cherry on top: diverse companies are more profitable, according to a 2009 study by the American Sociological Association. Their research found that companies that are more diverse in terms of race and gender have more sales revenue and higher customer numbers. As racial and gender diversity levels increase, profit relative to competitors also increases. These findings are backed by studies by McKinsey in 2015 and 2018, in which a correlation was found between profitability and diversity in terms of gender, ethnic, and cultural background. Diverse teams are more likely to outperform their peers on profitability.

And so, as Linda Fisk concludes:

“It’s increasingly clear that a commitment to equity is not just the right thing to do, but it is also smart leadership and good business.”

Sources

- Deloitte & Victorian Equal Opportunity & Human Rights Commission. (2013, May). Waiter, is that inclusion in my soup? A new recipe to improve business performance. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/human-capital/deloitte-au-hc-diversity-inclusion-soup-0513.pdf

- Fisk, L. (2021, January 4). Embracing Diversity And Inclusion As A Sustainable, Competitive Advantage. Forbes. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2021/01/04/embracing-diversity-and-inclusion-as-a-sustainable-competitive-advantage/?sh=4800d5482642

- Hunt, V., Layton, D., & Prince, S. (2015, February). Diversity Matters. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/insights/organization/~/media/2497d4ae4b534ee89d929cc6e3aea485.ashx

- Hunt, V., Prince, S., Dixon-Fyle, S., & Yee, L. (2018, January). Delivering through Diversity. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/organization/our%20insights/delivering%20through%20diversity/delivering-through-diversity_full-report.ashx

- Larson, E. (2017, September 21). New Research: Diversity + Inclusion = Better Decision Making At Work. Forbes. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/eriklarson/2017/09/21/new-research-diversity-inclusion-better-decision-making-at-work/?sh=4600e664cbfa

- Lorenzo, R., Voigt, N., Schetelig, K., Zawadzki, A., Welpe, I., & Brosi, P. (2017, April 26). The Mix That Matters. Innovation Through Diversity. BCG. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.bcg.com/publications/2017/people-organization-leadership-talent-innovation-through-diversity-mix-that-matters

- American Sociological Association. (2009, April 3). Diversity Linked To Increased Sales Revenue And Profits, More Customers. ScienceDaily. Retrieved February 16, 2022 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/03/090331091252.htm